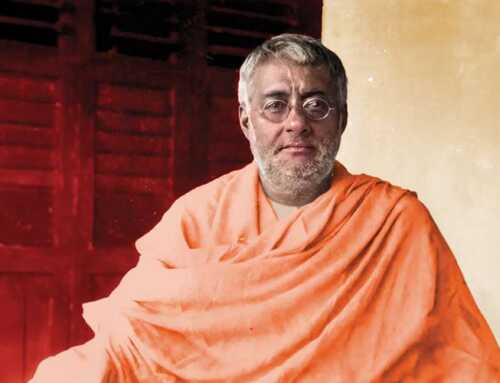

Swami Akhandanandaji Maharaj was a brother disciple of Swami Vivekananda. This article has been compiled from his book ‘From Holy Wanderings to Service of God in Man’ published by Shri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai, 2009 (Pg. 27-42)

Swamiji’s Wish To Travel Alone

Swamiji left alone for Delhi. Ten days after, others followed him.

When Swamıji left for Delhi, I said. “It was at your bidding that I gave up the idea of a journey to Central Asia and went back to Baranagar, and you now leave me!” “The company of Gurubhais,” said Swamiji, “is a great obstacle to the practice of Tapasya. Don’t you see, you fell ill at Tihiri and I could not undertake spiritual practices. I cannot undertake them unless I sever the tie of brothers-in-faith. Whenever I think of Tapasya, the Master sends an obstacle. This time I shall move alone. Nobody will know my whereabouts.” “Go you to the nether word!” said I, “but none-the-less I shall find you out, or my name is not Gangadhar!”

From Delhi, Sarat Maharaj and Sanyal went to Etawah, Rakhal Maharaj and Hari Maharaj to the Punjab, and I to Brindavan-Vrajadham. During my stay of three or four months there, I had an attack of bronchitis. Tulsi Maharaj now came to Brindavan. I accompanied him to Etawah via Agra.

At Etawah I was ill for five months. When Swami Trigunatita came, Tulsi Maharaj left for the Math, and I came to Agra with Swami Trigunatita. He left for Braja and I went to Jaipur to find out Swamiji.

At Gopinathji’s temple at Jaipur, I met Sardar Chatur Singh. I learnt from him that Swamiji had stayed at Khetri for two or three months after initiating the Rajah there, and then left for Ajmir. I visited Jaipur and went on to Ajmir.

At Ajmir

Sardar Chatur Singh sent an old relative of his with me to Ajmir. In the train the old gentleman took out grains of opium from a pouch and gulped them and began dozing with his eyes closed. “What is there in your pouch?” I asked. The answer was “Amal” (opium). “You take a lot of it?” I queried, “what are the benefits of opium?” “It has four qualities,” said the old man with his eyes shut. “What are they?” I asked. “A dog never bites an Amli (opium-eater),” said he, “he is never drowned, no thief gets into his house; and a woman can never cast her spell on him.” The reason is an opium-eater always walks with a stick in his hand, he scarcely uses water, he keeps awake the whole night-so no thief can come in, and so on.

He then expressed his grief thus, “Maharaj, I am not well off as in the British regime.” On being asked the reason, he added, “This is how it stands: We had lands. It being now partitioned, my share has become nil. But the family has to be maintained. In olden days I would go out with my sword and would earn something.” “How could you?” asked I. “I took to highway robbery,” said he, “and found the wherewithal for my expenses for some time. Again when need arose, I became a highway man. Thus things went on, Maharaj. But now under the British rule that is not possible.”

At Ajmir I learnt that Swamiji had left for Ahmedabad. I came to Pushkar. There I met Sarada (Trigunatita) and we went back to Ajmir. Here Sarada fell ill and I had to nurse him. Thus we had to stay there a fortnight,

After he came round, Sarada desired to move to Khandwa. Both of us were penniless. For myself I had no worry, but Sarada was too weak to walk on. For shame I could not beg money. I only said to the Bengali Babus, “Sirs, we shall leave day after tomorrow.”

My expectation was that hearing that we were leaving, they would of themselves offer to pay the railway fare. “All right, Sir, all right,” said they, but none offered to pay a farthing. ‘The day after tomorrow’ was approaching and then actually dawned. Then I said, “We shall start tomorrow.” The reply was, “All right, Sir, all right,” as before.

I had taken the vow of travelling with an empty purse. If anybody came forward with the railway fare, I would not accept the money-he was allowed only to purchase a railway ticket for me. But the ‘All right’ of the Babus of Ajmir worried me.

The first time I came to Ajmir, Maur Singh, brother-in-law of Chatur Singh, bowed before me and offered me some money. I did not touch the money. Now I thought of going to him with the request that he should purchase a railway ticket for Sarada. I did so. At my request, Maur Singh forthwith paid the fare for Khandwa. As I took the money, I regretted that I had once despised the boon of Lakshmi (goddess of fortune). Alas! I had now to tie the coins in my Pagri (turban). I then sent Sarada to Khandwa.

Mr. Williams: A Devotee of Christ

At Ajmir, I met Mr. Williams, a Christian. He took Sri Ramakrishna for an incarnation of Jesus. As he met me, he began to talk of the Master thus, “The first day I came to the Master, he spread a mat for me and had another spread for himself. ‘Look here, the two mats are an inch apart,’ said he. ‘The two mats are apart,’ said I, ‘but there is no distance between our hearts.'” On seeing the Master, the thought of Jesus became uppermost in him and he had much spiritual inspiration.

Rajputana, Abu, Gujarat, Baroda

After Sarada had been given the send off, my thought was, “Walking on foot I cannot get hold of Swamiji. But how can I travel by rail?” Accidentally someone paid eight annas and I was booked for Biawar. There I heard that Swamiji had come and left for Ajmir. From Biawar I started for Abu. I had to travel just as people paid my railway fare. After I had visited the places of interest at Abu, I left for Ahmedabad. There I learnt that Swamiji had left for Oadhoan (Gujarat). A gentleman took me from Ahmedabad to Dakore (Gujarat). From there I went to the Bay of Cambay via Baroda and Broach, and had a dip in the confluence of the Narmada.

At the Confluence of the Narmada

At the confluence of the Narmada, I was received as a guest at the house of a farmer in a village. After the noon day meal, the master of the house with the whole family went to the field to gather crops after lodging me in a good room. The whole house was left open. On finding them absent the whole day long, I thought, “What a profound trust have they! They go away entrusting the whole house to an unknown Sannyasi!”

At sunset they came back. I said to the old housewife, “Mother, I am an unknown man. How is it that you have so much confidence in me that you left the whole house to me the whole day long?” In reply she said, “My boy, a few days back we went to the field leaving a Sannyasi like you at home. We came back to find the Sannyasi had left. We searched for him, but he was nowhere to be found. I remembered that there was a silver bangle worth thirty rupees under the mattress on the cot on which the Sannyasi sat. It was found that the bangle had gone with the Sannyasi. It is the duty of the householder to take one in the garb of a Sannyasi as a real Sannyasi; one fails in ones’s duty if one thinks him fake. In placing confidence in him, I have done what a householder should do, but the Sannyasi failed to keep his vow. I lost a bangle worth thirty rupees, but it has not made me a pauper.”

Baroda

From the confluence I came back to Baroda and spent a night at the house of a cultivator. Next day, the Maharashtriya Brahmanas said, “How is it that you, a Dandi Sannyasi, are living with a Sudra?” They took me to a Brahmana’s house where I was received very kindly. But as the house was very unclean, I was in search of a suitable place.

In the State of Baroda, a Sannyasi cannot be lodged in a Siva or a Vishnu temple. I saw a nice house where I thought, I could be comfortable. It belonged to the Baroda State. A high Bengali officer occupied it. He was not at home then.

I went out to find him. When I met him, I found him very kind and obliging. He took me to his house and said, “I live here alone. Many of the rooms are vacant. You may stay in any one of them you like.”

He sent a man to fetch fruits and sweets for me. “Do you believe in caste?” he asked. “No, how can I?” said I, “I am a Sannyasi.” The gentleman then recalled the servant who had been asked to fetch sweets for me and said, “Why should you then take bazaar sweets? You may dine with me.” I agreed.

But when the food came, the sight of the man who served it disgusted me. He was a Goanese Christian. His costume and ways filled me with repulsion, and I lost all appetite. Tea was served first, I somehow gulped some of it. But the memory of the hand that catered the ‘nectar’ brought about a feeling of nausea. Rice and curry followed, and I sought some pretext for leaving the table. My host sat at the same table, and it would be a breach of etiquette to leave it in a huff”. But queasiness soon overpowered etiquette, and I heard the whisper in my ears, “Send a grain of that rice within, and all the food you have taken from your Annaprasana (the first rice-taking by a child) will be pushed out!” I was compelled to tell the gentleman, “I can’t carry on any longer. I am feeling sick, may I go out?” The gentleman looked at me with surprise and said gravely, “I see, you have not yet been able to cast off caste prejudice. You still seem to believe in caste.”

“Yes Sir. I am what I am,” said I. Then an arrangement was made that I should dine with a Maharashtra Brahmana and live with this gentleman.

Ahmedabad, Junagadh, Prabhas, Dwaraka, and Cutch-Mandavi

I stayed a fortnight at Baroda and left for Ahmedabad. The gentleman paid the railway fare. At Ahmedabad I got a Sannyasi as a companion who offered to take me by railway train and drop me wherever I liked.

At Oadhoan junction I met a gentleman from whom, on enquiry, I learnt that a learned Sannyasi named Vivekananda was staying at Junagadh. So my Sannyasi companion got me booked for Junagadh.

At Junagadh I learnt that four or five days back Swamiji had left Porbandar for Dwaraka. After I had seen the objects of interest at Junagadh, I left for the holy place of Prabhas. From there I took the steamer at Verawal to go to Dwaraka. There I learnt that Swamiji had left for Vetdwaraka. Staying a night at Dwaraka, I left for that place. There I got the news that at Verawal, Swamiji had got an invitation from the Prince of Cutch-Bhuj to visit his place and had accordingly gone to Cutch-Mandavi. Forthwith I left for Cutch-Mandavi.

Even after such long pursuit I could not reach Swamiji, and my eagerness rose to such a pitch that I left for Mandavi without caring to see objects of interest at these places. There I learnt that Swamiji had gone to Narayan Sarovar. Spending a night at Mandavi, I started on foot towards Narayan Sarovar.

Towards Narayan Sarovar

At a village eight miles from Mandavi, a householder said, “Swamiji, your path is infested with highwaymen. Swami Vivekananda has the Prince’s men with him; but how could you go alone?” “I have nothing with me, the robbers can expect nothing from me,” I replied. “Well, to move from village to village,” said he, “you may have a bullock-cart. Why don’t you take a guide also?” I did so.

A boy was my guide. On the way my thought was, “If robbers attack me, I shall say, ‘Take everything I have, please do not kill me.’ But I do not know the dialect of the Cutch people, and probably they may not understand my Hindi too.” So I asked the guide, “‘Take whatever I have, only do not kill me,’ – how would you express it in the Cutch language?” “You say, Babaji,” said the boy, “Mere gano, muke maryo mu.” I repeated it as I went along.

As ill luck would have it, I found I would have to wait too long at the next village to secure a guide. So I sent off the boy and proceeded alone. Fifty miles I tramped along in safety. Narayan Sarovar was still thirty miles away, but now my way lay through villages, most of which were deserted because of famine.

As evening fell, I found men in a village, and I spent that night there. Narayan Sarovar was fourteen miles away and it could be reached along two ways—one by a foot track and the other by a track for carts. The foot track was twelve miles long. It was safe and there was a village too, on it. Those who went to Narayan Sarovar on foot chose this track. But the other path was absolutely solitary without a human habitation nearby. So the foot track was preferable. But my idea was: Swamiji had gone in the cart and was sure to return by cart. If he came back by the cart road while I was on the foot-track, for a mere fourteen miles I would be missing him. Having come so far, it would be a tragedy to miss him. So I should rather take the cart road.

On finding me ready to go along that way, a shopkeeper said, “You will find no habitation on your way. At noon you will reach Zamanwara Talao (tank). Have a dip there. Please take this fried rice and molasses for your breakfast.”

Here an up-country man, a Tairthik Bhakat (a pilgrim devotee) joined me. “Why do you take this way infested by highwaymen?” l asked. In reply he said, “I find great pleasure in your holy company.” Though an up-countryman, the Bhakat was very sickly; he carried a worn-out long bag, with both ends open. We walked together.

There were open plains on both sides. It was solitary; there was no trace of a human habitation. About the middle of the way in the noon, we came to the above—mentioned tank. We took a bath and shared the fried rice and molasses given by the shopkeeper. As he ate the fried rice, the Bhakat said, “Maharaj, do tikkar laga lun (let me make two loaves of thick bread).” This surprised me. How could we have ‘tikkar’ here? “Where will you have flour to make tikkar ?” I asked.

As if by magic the Bhakat brought out of that worn-out bag half a seer flour, a pan, salt etc., and strolling out here and there procured some dried cowdung. The expert hands of the Bhakat took no time to make tikkar.

We were taking bread with molasses when there came a shepherd boy with some goats and sheep. “Let Maharaj have some milk,” said he, “he is taking bread dry.” “All right, milk them if you can,” said the boy. At once from the magic bag came out the cup, in which he drew near about half a seer of milk. I shall never forget in my life how the tikkar with molasses in milk tasted. After our meal the utensils were scoured and put back into the bag. We were on our path again.

In the Hands of Robbers

It was afternoon. As we walked, I marked four men following us some way off our path. The plain was alluvial, and the men were sometimes visible and sometimes hidden from our view. I suspected them to be highwaymen.

The sickly Bhakat had lagged behind. I thought of advising him to take to his heels, for he had his bag and possibly money too. But my next thought was, where could he escape? Also my shouting would reach the ears of the robbers. Let us walk as we have been doing, leaving things in the hands of the Master.

Again I thought, “One of the men has a blanket on and a red turban on the head. I have seen at Calcutta, policemen with blanket and red turban. They may be guards of some Zamindar (landlord).” But such doubts were soon dispelled. As I proceeded, I saw that the four robbers or sepoys had marched cross-country along the plain and were on my way, in front of me. “How far is Narayan Sarovar?” asked I. They were moving. One of them stopped and said, “Six miles.” Next, all of them stood blocking our way. In the meantime I came near and was about to ask, “Are you robbers? Do you rob people? But scarcely had a word escaped my lips when one placed his hands on my shoulder and thrust me aside. At once I said, “Mere gano, mere gano, make maryo mu, (Take whatever I have, only don’t kill me).” At once, a stick landed on my back twice. By the grace of God the sticks was of thin bamboo and I had a coat stuffed with cotton, and there was a bundle on my back containing clothes, a book, a tiger’s skin and other things.

As I lay on my back, I saw the four men had not the appearance I had seen before. Their faces had undergone a distortion, the eyes had become red with the balls rolling, Two of them held naked swords shining in the sun. An old man thundered in a rough tone, “Lugra Khol (strip off your clothes).” At once I threw all my clothes except the koupin (loin-cloth) and went on repeating-“Mere gano, Mere gano, muke maryo mu.”

The robbers made a thorough search of my clothes and the pockets of my Alkhalla (long coat). In the meantime there appeared the Bhakat. Frightened by the terrible and the naked swords, he uttered in a piteous tone, “Ham to gaye (I am undone).”

A weakling, he was trembling all over. The bowl in his hand and the bag on his shoulder had slipped off. The tongue had protruded, and trembling he sat down on the road.

At the sight of his face, distorted with fear, I could not help smiling even in that dire peril. But at once I told the robbers, “The force with which you thrust me will kill this weakling, don’t lay hands on him.” “Hand over all you have to them,” I said to the Bhakat. “I shall see to it that you get utensils and other things once again.” He was not the man to pay heed to my words or to believe me. With folded hands he prayed to the robbers, “My friends, do not seize these articles of a poor fellow. If I miss them, l shall never recover them.” I saw the poor fellow was more attached to his worn-out bag than to his life.

On the other hand, as the robbers found a tiger’s skin and some books only in the pockets of my Alkhalla and a bundle on my back, they were sure that the Sannayasi had only an empty purse. They then moved towards the Bhakat, but seeing the condition of his bag, stopped and did not even touch it.

They then consulted among themselves and ordered me to fold my hands behind my back so that they might bind them. But by that time I had regained my courage. I said in a clear tone, “No, I shall not place my hands as you say.” The robbers had sheathed their swords, but they unsheathed them slightly, and said. “Unless you bring your hands at the back, they will be cut off forthwith.” “Do as you like, I won’t bring my hands at the back.” I said firmly.

Then they took my turban and began to bind my hands together with it. But before they had finished doing so, and were about to leave, I said, “Hallo, take these warm clothes. You are poor, they will be of use in winter. No one will find you out, nor shall I tell anybody.” But the fellow wearing a red turban and a blanket touched my foot and said, “Dua karo, Maharaj, kapra pindh Io (You may go, Maharaj, put on the clothes).” By placing his finger on the lips, he signed to me not to divulge the incident to anybody. I still repeated, “Take those warm clothes.” But forthwith they vanished as fast as their legs could carry them.

From Narayan Sarovar to Ashapuri

After the robbers had departed, I wended my way slowly with the Bhakat. Before we had passed some two miles, we met a group of Vaishnava Sadhus, some twenty five in number, coming back after pilgrimage. Bhakat began to chat with them. I walked on.

At nightfall I reached Narayan Sarovar only to learn that on the previous day Swamiji had gone to the seat of the goddess Ashapuri by a different route.

The shock from the attack of the robbers and depression brought on me a fever at Narayan Sarovar. Afterwards the Mahanta (chief priest) said to me, “Yours is a rebirth; you would not have been alive now, if you had had only five rupees in your purse. At that very spot they once killed a man for a trifling sum of thirty rupees.”

On account of my fever I could not bathe at Narayan Sarovar. The Mahanta Brahmachari (the celibate chief priest) gave me a guard and a horse. I went on horseback with the guard.

From Narayan Sarovar I came to the sacred place of Kotishwar Mahadev. Kotishwar is in the extreme west of India. The Arabian Sea washes its shores. Kotishwar is a Lingam. Here Saivas (worshippers of Siva) stamp their arms with hot coins. From Kotishwar I started for Ashapuri.

On our way to Ashapuri, the guard pointed towards a village and said, “The people here are highwaymen.” At Ashapuri I dismissed the guard and the horse. Here I was informed that Swamiji had moved on to Mandavi.

At Ashapuri I spent a night. A large stone besmeared with vermillion-that was the seat of the goddess. Ashapuri marks the north-eastern boundary of Cutch and is very near to Baluchistan. It is famous for its incense.

The ways of the priests of the Goddess are like those of Musulmans. They do not tie their dhoti on the backside. They are called Kapadis. They are fond of garlic and chicken, and use no sacred thread. Ashapuri village is very sparsely populated. It is desert all around. Rainfall is very scanty.

The Kapadis (priests) hired a camel with a driver for me. They took me to the next village. Likewise, the Zamindar (the local feudatory of the Prince of Cutch) of every village I passed through got me a horse and a guide to take me from village to village.

On Horse-back

Thus I came to a village where the Diwan (steward) of the Zamindar advised me, “The days are very hot. You should rather travel at night.” He gave me a horse and a guide. Between that village and the next, there was an extensive field infested with highwaymen. A month back a girl was going from her father’s place to her father-in-law’s. She was waylaid, robbed and killed.

At midnight we were at the centre of the plain when the guard suddenly stopped and looked about. On my enquiring about the reason, his reply was, “A bad man hides himself behind a tree.” I was rather scared to hear it. But the guard reassured me saying, “Don’t be afraid, I too belong to their gang. So long as I am with you, nobody will do you harm.”

“How is it that you are one of them?” I asked. “How can I help it; your Holiness?” he replied. “The pay I get at the Zamindar’s Office is too meagre. So sometimes I have to join the gang of robbers.”

Out of sheer fright I took the name of God to save myself. A robber protected me! But the guard cheered me up. Towards daybreak we got to a village where I was lodged in a Dharmashala (a temporary abode for travellers).

The guard expressed his remorse thus: “It is not at all good to be on the road with a Sadhu. Had you, a Sadhu, not been here, my horse would not go without its fodder. There is hay enough inside the house, and but for your presence, I would easily have scaled the wall and stolen it.’

The men of Cutch have a great devotion for Sadhus. If a Sadhu becomes their guest, they would feed him as sumptuously as they would a near kinsman. If a Sadhu comes into the village, the people will wrangle as to whose guest he is to be. Each of them will lay claim to the privilege of being his host.

Meeting with Swamiji at Mandavi

Riding sometimes on a camel and sometimes on a horse, I at last reached Mandavi with the guard. There I had the news that Swamiji was residing with a Bhatia (a man of Cutch). I lost no time in reaching there.

I saw that Swamiji had undergone a great change in his appearance. His beauty illuminated the whole room. He was startled to see me there. He listened to all that I had experienced on the way. It filled him with apprehension, and he said, “Gangadhar has braved all these dangers and has pursued me even at the risk of his life. Surely he will never give up haunting my company. But I have a plan which I cannot realise if any of my Gurubhais be in my company.”

But I was obstinate. At last Swamiji said, “Look here, I have become a bad man! Leave my company.” I replied, “Who cares if you have become bad? I love you. I am not concerned with your conduct. But I won’t stand in your way. I was so anxious to see you. My anxiety has been allayed. Now you may go alone.”

Swamiji was glad to hear this. The very next day he left for Bhuj. I did not join his company. I waited a day before I started for Bhuj. Swamiji was now sure that I would not intrude upon his freedom.

Sadhu Ananda Ashram

At Bhuj, Swamiji said to me, “The Raja here is paying us too much attention, and that may be an eyesore to many if we stay here long. Twentyfive years ago a Bengali Sanyasi named Ananda Ashram came to Bhuj and helped much in the improvement of the State. At that time it was a custom with the Prince to lease out villages. The lessee would extort from the tenants several times the amount to be paid to the Prince as revenue. The tenants were thus much tortured. On Ananda Ashram’s advice the Prince abolished that custom and introduced the good system that obtains in the British Raj. The State is still ruled in the manner introduced by him. But such reforms did not find favour in the eyes of the State Officers. Ananda Ashram became their eyesore. His enemies mixed poison with his food and killed him. We may have the same fate. Let us move off even tomorrow.”

Separation from Swamiji

From Bhuj, we two came back to Mandavi and stayed there a fortnight. Next Swamiji started for Porbandar, and five or six days after, I followed. There we met again.

Here Swamiji was a guest at Shankar Pandurang’s place. He was the governor of Porbandar (Sudamapuri). Swamiji said that in the whole of India he had not seen Pandurang’s equal in Vedic learning. As a commentary on Atharva Veda was not available, he compiled one himself. Swamiji used to speak with him in Sanskrit and in a short time became an adept in it.

From Porbandar, Swamiji went to Junagadh, and I to Kathiawad. I passed through Jetpur, Gondal and Rajkot, and came to Jamnagar. A terrible storm overtook me on my way to Jamnagar. Here I lived for a year.

Your Content Goes Here